Private companies and ‘shadow banks’ may be incubating climate risks out of sight of financial regulators and traditional financial institutions

“The brighter the light, the darker the shadow”. It’s a metaphor regulators would do well to contemplate in their efforts to harden the financial system to climate risks.

As official scrutiny of the carbon-intensive exposures held by public companies and regulated financial institutions has intensified in recent years, so has an appreciation that opaque private markets and unregulated firms may incubate huge climate risks of their own. BlackRock chief Larry Fink went so far as to describe it as “the biggest capital markets arbitrage in my lifetime”:

“We are seeing more hydrocarbons moving away from public entities to private entities … If we’re serious about this . . . we have to ask all of society to move forward or we’re lying to ourselves, we will not get to a net zero”

Some regulators are waking up to this dynamic. In a speech last month, Caroline Crenshaw of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) said that it is “critical” that policies to encourage divestment from carbon-intensive activities “consider the growing expansion of the private markets”. She added that stakeholders should work together to “ensure that the externalities high-carbon emitters put on our environment and in our capital markets do not find relative safe haven in areas of darkness, least resistance, and lowest cost”.

One data point from the SEC underscores the size of these “areas of darkness”. In 2019 alone, it estimated that $2.7 trillion was raised by private issuers through so-called “exempt offerings”, compared with $1.2 trillion by public issuers.

However, in the US regulatory authority over private markets is limited, impairing officials’ efforts to tackle the climate risks that lurk in the shadows. Right now the SEC is seeking to change this with a plan to make more private companies regularly disclose financial and operational information. Commissioner Allison Herren Lee framed the push as a way for investors, employees, regulators, and the public to gain insights into big private firms that “can have a huge impact on thousands of people’s lives”. However, it would also obviously improve regulators’ visibility on private companies climate risks.

Expanding regulatory scrutiny to private markets may prove challenging. Entrenched interests in business and politics are already pushing back against the SEC’s yet-to-be-launched proposal, the Wall Street Journal reports. However, while this particular fight gears up, there are other ways in which regulators could combat the climate risks that lurk in the shadows.

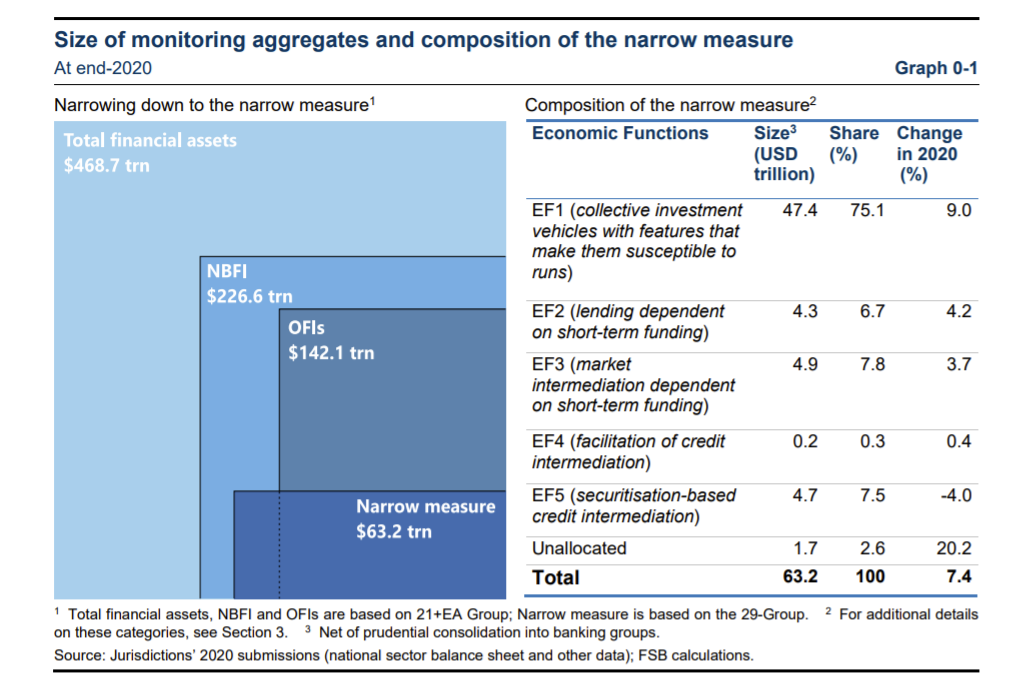

One option could be ratcheting up the scrutiny of unregulated, private financial institutions and their interconnectedness with traditional lenders. Worldwide, ‘shadow banks’ — entities which extend loans and credit outside the umbrella of bank regulation —accounted for $63.2 trillion of global financial assets, about 13% of the total, in 2020 according to “the narrow measure” used by the Financial Stability Board (FSB).

Source: Financial Stability Board

Though these entities are not classified as ‘banks’, they are often deeply interconnected with traditional lenders through wholesale funding instruments, direct loans, and deposits. These relationships mean that unregulated shadow banks can transmit risks into the regulated financial system, thereby amplifying market shocks. For example, in its 2021 annual report, the US Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) explained that ‘non-bank financial intermediaries’ (another term for shadow banks) elevated “liquidity pressures in the financial system” during the market turmoil of March 2020.

Because of these kinds of threats, regulators would be negligent if they failed to take steps to ensure that shadow banks and the risks they pose — including climate risks — were appropriately managed.

What would regulatory action in this area look like? A recent report by the left-leaning Center for American Progress offers one idea. The FSOC — which is made up of all the major US federal financial regulators — could factor climate risk into the process it uses to determine whether shadow banks pose a threat to US economic and financial stability. This could lead to those shadow banks that are loaded with carbon-intensive exposures being labelled as systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) under the Dodd-Frank Act. A SIFI designation in turn causes an entity to fall under the supervision and regulation of the Federal Reserve. The Fed could then apply enhanced supervision measures on these SIFIs, including capital requirements. Doing so could improve the safety and soundness of high-risk shadow banks and limit their threat to the traditional banking sector.

To complement this regulation, federal agencies could also ratchet up the regulatory capital charges applied to traditional lenders’ investments in those shadow bank SIFIs that are loaded with climate risks. Increased liquidity buffer requirements to cover funding exposures to these entities could be enforced, too.

Under existing regulations, US banks already have to calibrate the amount of liquid assets they must hold to reflect the amount and quality of short-term funding they acquire. Increasing the regulatory weighting applied to funding received from shadow bank SIFIs (and that provided by traditional lenders to SIFIs) would therefore compel traditional lenders to hold a bigger liquidity buffer against the risk that such funding could be pulled at short notice, or that their short-term loans to shadow banks go unrepaid.

As it stands, the FSOC has yet to consider shadow bank climate risks. In its 2021 report, the council did not put forward any recommendations that explicitly reference these entities. However, that may change soon. In December, the FSOC voted to establish the Climate-related Financial Risk Committee (CFRC), with a mandate to “identify priority areas for assessing and mitigating climate-related risks to the financial system”. If it does its job right, this should lead the committee to consider those climate risks lurking within shadow banks and communicate these to the broader FSOC.

Market-led initiatives could also be harnessed to tackle shadow bank climate risks. The Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) offers one solution through its global carbon accounting standard. This lays out a framework for financial institutions to measure and disclose their financed emissions: those generated through their debt and equity investments in non-financial companies. Right now, this framework covers six asset classes, including business loans, and PCAF is working on more. One area it could turn its attention to are the emissions financed by traditional lenders through their lending and investing relationships with shadow banks.

Clearly, traditional lenders would have to be able to ‘look through’ into their shadow bank counterparties’ portfolios to get data on their financed emissions first. Recalcitrant firms that are under no obligation to disclose such data may deny such requests, of course, but their lenders/investors could always put the screws on them, and demand such information as a condition for doing business. This isn’t a far-fetched outcome. Already, buy-side traders, like asset managers and pension funds, are starting to consider ESG factors in their choice of bank trading counterparties. Why shouldn’t lenders, then, consider emissions factors in their choice of shadow bank trading partners?

Such entities need not hand over detailed portfolio positions, either. The PCAF standard can be used to estimate financed emissions using data of varying granularity. If the economic sectors invested in by a shadow bank are known, and their respective allocations in their portfolio understood, that’s enough to start with.

And a start is what’s needed. Otherwise traditional lenders risk undercounting their own carbon risks, and in turn external stakeholders — including financial regulators — will get a warped view of the financial system’s overall vulnerability to climate change. For the sake of financial stability, what takes place in the shadows must be brought to light.